By Eric Wagner

Reviewed by Ann Hedreen

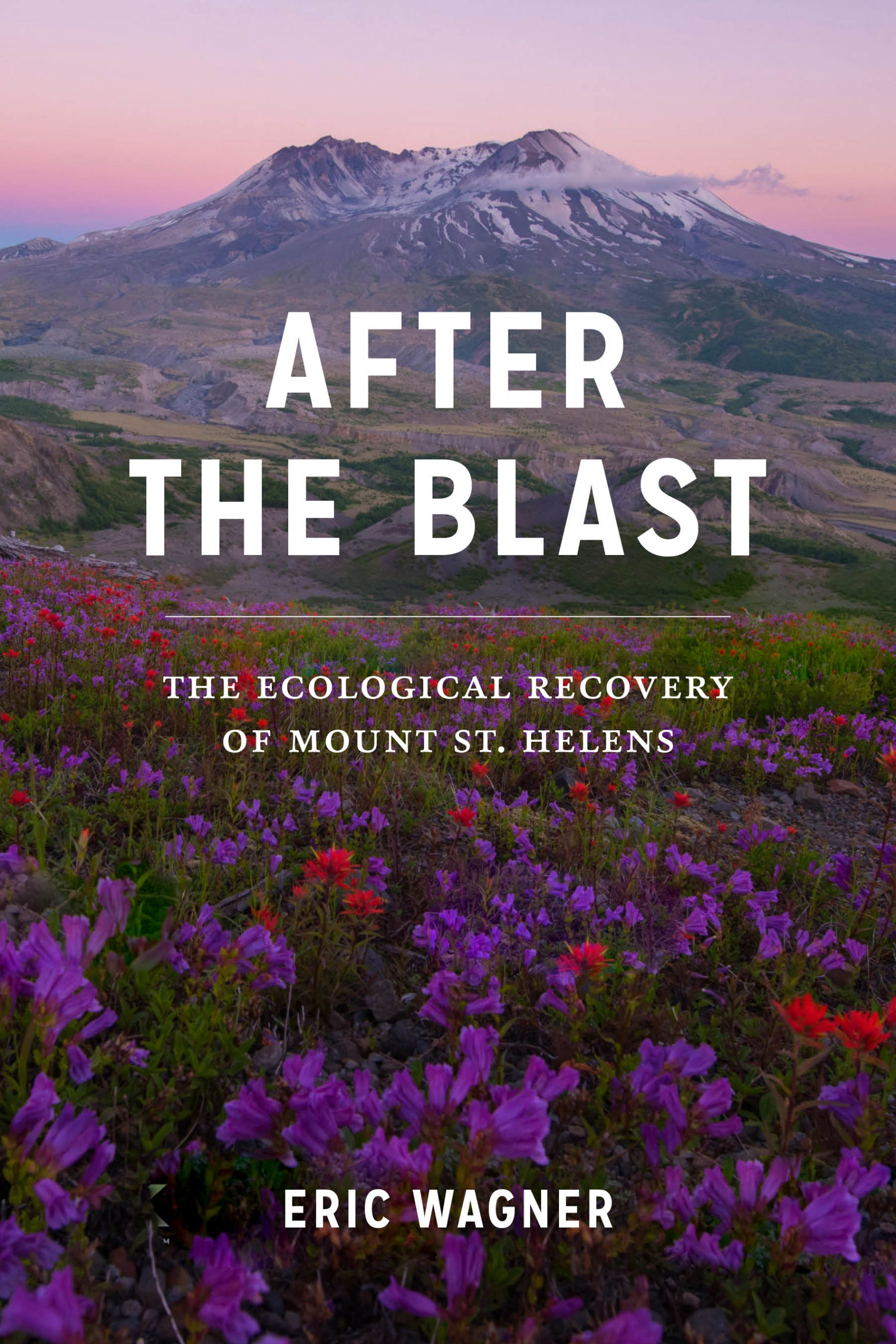

In early February, aka one million years ago, I requested an advance copy of After the Blast: The Ecological Recovery of Mount St. Helens by Eric Wagner, published in April by University of Washington Press. I had been thinking about the upcoming 40th anniversary of Mount St. Helens’ May 18, 1980 eruption—an event which loomed large over my early years as a journalist, even though I had missed the main event—so I was thrilled to see Wagner’s book on the UW Press website.

In early February, aka one million years ago, I requested an advance copy of After the Blast: The Ecological Recovery of Mount St. Helens by Eric Wagner, published in April by University of Washington Press. I had been thinking about the upcoming 40th anniversary of Mount St. Helens’ May 18, 1980 eruption—an event which loomed large over my early years as a journalist, even though I had missed the main event—so I was thrilled to see Wagner’s book on the UW Press website.

Wagner, who earned a Ph.D. in biology from the University of Washington, has built a career as a science writer for magazines like The Atlantic, High Country News, Orion, and Smithsonian. He has authored a book about penguins and co-authored a book about the Duwamish River. I feared I might not be the right kind of reader for his kind of writing. Turns out, I’m exactly the right kind of reader: an English major who loves to read about science in language that is both comprehensible and confident.

“The summit rippled, churned, and then collapsed as more than two billion tons of rock, snow, and glacial ice fell away in the largest landslide recorded in human history,” Wagner writes, of the eruption that began at 8:32 a.m. on Sunday, May 18, 1980, lasted nine hours, and caused the deaths of 57 people. The fact that it happened on a Sunday morning is nearly always noted in the recounting of the Mount St. Helens story, because, as Wagner later tells us, “At 8:30 on a Monday morning, several hundred loggers would have been arriving for their shifts, the mountain ringing with the high whines of their chainsaws, the toots, and chirps of whistles. The lateral blast would have killed them all.”

He had me. I was all in, for all 222 pages, from the first purple flashes of fireweed popping up after the eruption right through the return to the point of eventual overabundance, of the Roosevelt elk. Wagner’s approach to this enormous story is to tell it through the scientists who showed up right after the blast and immediately understood the importance of embarking on long-term studies of its effects on everything: birds, insects, algae, lakes, streams, small plants, tall trees, trout, salmon, big mammals, tiny mammals, and the geology and continued volcanic activity of the mountain itself.

After the Blast begins with a prologue in which we meet the three US Forest Service scientists—Jerry Franklin, Jim Sedell and Fred Swanson—who, just two weeks after the eruption, were allowed a helicopter flyover and a brief touchdown: just long enough to see tiny plant shoots, beetles, ants, evidence of gophers, elk or deer, and one clear stream with a bit of algae in it. In those few minutes on the ground, they suddenly understood that their job would be not simply to measure the extent of the destruction, but to witness and interpret the recovery of the gouged and gashed mountain, once the most stunningly symmetric of all the volcanoes in the Cascade Range. (It’s also the youngest, at a mere 40 thousand years old. In contrast, Mt. Rainier is 500 thousand years old.)

Wagner then fast-forwards to 2015, when he attended a week-long gathering called the “Pulse:” an opportunity for scientists who have worked at Mount St. Helens to convene, once every five years, to gather data from research plots marked out decades ago, share their findings, eat, drink and brainstorm about what it all means and what might lie ahead for this still-volatile volcano. More than 100 people showed up in 2015. Wagner talked to many of them, including Fred Swanson, who loaned him his own dog-eared copy of what you could call the Old Testament of Mount St. Helens research: the 850-page US Geological Survey Professional Paper 1250, a collection of 62 individual papers published in 1981. Wagner parses “1250,” as it’s known, for the rest of us, using it as his source for a blow-by-blow description of what happened on May 18, 1980, which sets us up well to understand the chapters that follow, about the regeneration of plants, animals, streams, and lakes in what is now officially the Mount St. Helens National Monument.

The regeneration of Mount St. Helens is an astonishing story. And in these times when we all want so badly for science to save us, it is a testament to the perseverance and patience of the busy, inquiring minds that make scientists who they are. The researchers we’re placing our hope in now need patience, too, as they search for clues to a Covid19 vaccine or cure, but of course, they do not have the option of watching their work unfold over decades.

Meanwhile, those of us who are not on the front lines of science, medicine, and essential work must cultivate levels of patience we never thought possible. For some, that means patience with children and online learning, and/or patience with a job conducted on Zoom from a cramped corner of a bedroom. For many, it means no work, less work, or at the very least a sudden bounty of time formerly spent commuting or going out. And the only kind of travel we’re doing right now is the armchair kind. For lovers of wild places, After the Blast is an armchair journey you won’t want to miss.

Ann Hedreen is a writer, filmmaker, and the author of Her Beautiful Brain, winner of a 2016 Next Generation Indie book award. Ann and her husband, Rustin Thompson, own White Noise Productions and have made more than 150 short films and five feature documentaries together, including Quick Brown Fox: an Alzheimer’s Story. Ann has just completed a second memoir called After Ecstasy: Memoir of an Observant Doubter.