I recall a conversation I had with a very creative friend. He worked at a highly respected television production company, but he hated his job. To help him feel better, I made a rather stupid and ageist comment: “Well, at least you get to work with a lot of creative young people.”

“You know,” he replied, “the young employees aren’t that creative. They are too young. They’ve learned one successful trick and are too scared to try anything else.”

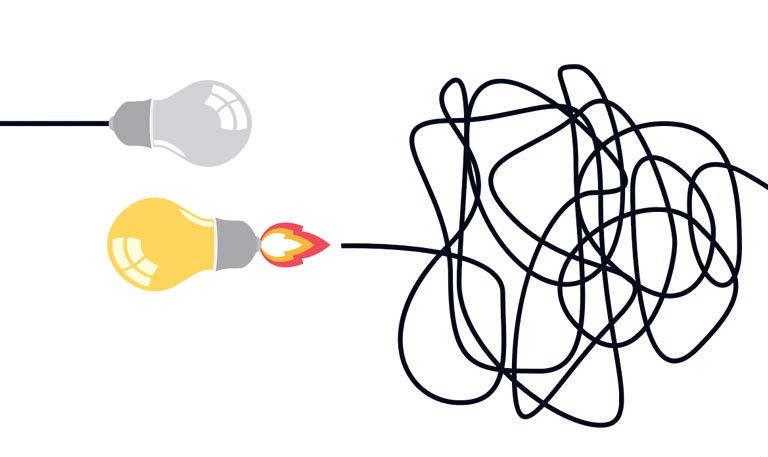

Creativity is a dynamic partnership between novelty and routine. The two perform a fluid dance in which neither one leads or dominates for too long. Successful creativity requires flights of the imagination coupled with the stability of process and procedure.

One basic formula for creativity is to use novelty to come up with a useful idea that is then turned into a routine. Then, come up with another good idea that can be turned into another routine. Repeat and repeat again. Along the way, you check and monitor your routines to see if they still work. Discard them if they don’t and replace them with new routines that you’ll check and monitor. That’s how our evolved problem-solving algorithms are refined through experience.

The young people who worked with my friend were stuck using the one creative routine they had managed to discover. They had neither the wisdom nor confidence to be truly creative. True creativity—mature creativity—is a constant process of reinvention that generates an endless supply of creative routines.

Creativity is usually defined as the process of bringing something new into the world that is useful and adds value. Novel ideas are important, but they also must be useful and of value. Flights of imagination can be hugely entertaining, but they aren’t truly creative unless they are converted into actionable steps that we can use to make our lives more comfortable and meaningful.

Creativity is a multi-step process. The cherished Eureka moment—the “a-ha!” reaction, that flash of insight—is intoxicating, but it is only one step in the process of turning ideas into useful and valuable tools. It takes maturity and patience to work through the entire creative process. This is especially true with complex projects. It takes time, and myriad creative cycles, to accumulate the broad and diverse array of useful routines you need to generate creative options.

Steven Jobs offered us this: “Creativity is just connecting things.” Creativity is knowing how to connect the dots in new and useful ways. The more “dots” you have in mind and at your disposal, the more chances you have to find new, interesting, and useful combinations.

Mature creativity thrives because you’ve had time to accumulate a wealth of useful routines. Mature creativity is powerful because the growing portfolio of routines can be refined and improved through trial-and-error testing. Mature creativity is effective because we learn what routines work best and, with that experience, develop the mastery to deploy them effectively.

Age alone is no guarantee of creative power. Without wisdom, curiosity, and a fascination with change, the dominance of routines can become stultifying. If we aren’t careful, this trend toward automatic routine can take over our lives and stifle creative living. If we get lazy and allow routines to dominate, the delicate dance between process and innovation is disrupted. Novelty, exploration, experimentation, and curiosity are forced to sit out the dance. When this happens, we become the cliché of old dogs who can no longer learn new tricks.

Navigating the river of life requires constant creative adjustment. Keep your mature creativity alive and active in these ways:

- Stay curious. Continue to explore and question.

- Never believe that your current solution is the final solution.

- Discard obsolete, destructive, or obstructive routines.

- Continually replace worn-out ideas and routines with new and improved versions.

- Keep dancing.

Michael C. Patterson, founder and CEO of MINDRAMP Consulting, writes extensively on the art and science of brain health and mental flourishing. He is an educator and consultant who previously managed AARP’s Staying Sharp brain health program and helped develop the field of creative aging.