The World We Entered, The World We’ll Leave

“It was the best of times it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness.” – Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

As we age, there is an urge to feel we will time our dying well. As my mother would say, “The world is going to hell in a handbasket anyway.” My mother had lived through two world wars, a depression, immigration, poverty, domestic violence, and the death of two husbands. But she was quite sure she had lived at the best of times. Many elders think the same thing because that thought makes it easier to leave.

Looking back over our decades reminds us of how we have lived. We can imagine the future even if we don’t get to be there. Cultural anthropologists, like me, want to know more about what is ahead, so we study the beliefs, perceptions, and rituals of the past and present. In particular I wanted to understand what happens when change challenges a country or tribe’s culture.

Understanding changes in culture and society involves art, literature, language, psychology, sociology, technology, philosophy, and more. To order so much data, I think of the four corners of a jigsaw puzzle. With those corners, even without a picture on the box, we can compose the puzzle edges and maybe fill in the rest. The four corners of this cultural change puzzle are technology, economics, demography, and culture.

Society changes a lot when it discovers a new technology, whether it’s a new wheel or a new engine. There is a natural workforce shift, because agriculture and the internet require different skills. The shift changes who is hired, who earns money, and who has power. New workers often change demographics: who we encounter, at work and at home. Workers, management, and communities have had to adapt rapidly in recent decades because technology has forced our economy into a competitive global marketplace.

Societies accommodate shifts in technology and an increasingly diverse workforce, grumbling but willing, in order to survive. But cultural beliefs about the way things ought to be are harder to change if differences are too visible. We might welcome new cuisines, music, and dances, but hesitate when confronted with gender, skin color, body abnormalities, or unfamiliar religious fashions. Ambassadors in ethnic dress are usually respected, but maybe not as neighbors.

A traditional group may learn to tolerate newcomers but resist seeing them as fellow citizens. A tribe or class that feels it is losing power often becomes fearful and clings to stereotypes and intolerance. And this isn’t new: The invention of the forklift truck freed women to move heavy items, eliminating the strength differential but not the traditional belief that women are weaker.

When certain types of intelligence and skill became more energy efficient and more valuable than brute force, people perceived as “weaker” could compete. At the University of Washington medical school, where I taught in the 1970s, there were seven women in a class of 100. Now it is 53. The same is true for today’s law schools.

Psychologist Abraham Maslow tried to make sense of our ambivalent cultural reactions to the push of technological change. In 1943, he published his hierarchy of human development built on human needs. The bottom level of his pyramid were the things we need to survive: food, water, shelter, and reproduction. Meeting these needs only required a basic reptilian brain and extended family bands of hunters and gatherers.

The next level up, as tools made survival more probable, were groups able to subsist on horticulture, agriculture, and eventually the energy sources of coal and oil. Security needs could be met by forming communities, building forts, storage, and organizing for battle. The group, not the individual, was essential for stable survival. Death before dishonor defined both masculinity and femininity.

As people felt more secure and lived longer lives, Maslow’s next level up was a movement away from the traditional domination of the self by the group. As Americans began to feel safer after World War II, new ideas and questions about relationships, leisure, and personal identity gained credence. Hungry people have little time to ask themselves such questions. Well-fed people can worry about eating too much or whether they are happy, known, even loved.

Stability at one of Maslow’s levels is the gateway to the next. As women and minorities entered the workforce and proved their merit, it opened many minds to different ways of being. Americans, in particular, as an immigrant nation, began to shed the crippling fear of small human differences. These ancient anxieties, connected to the once legitimate fear that small family bands had of strangers, did and still do allow wars, slavery, the harassment of minorities, and domestic abuse.

If we can make a group “the other” or “them,” we can kill them. If success—in our new techie diverse workforce—requires higher levels of social and emotional intelligence, then the cultural fabric has to be unraveled and rewoven. These tensions and battles are still being played out around us.

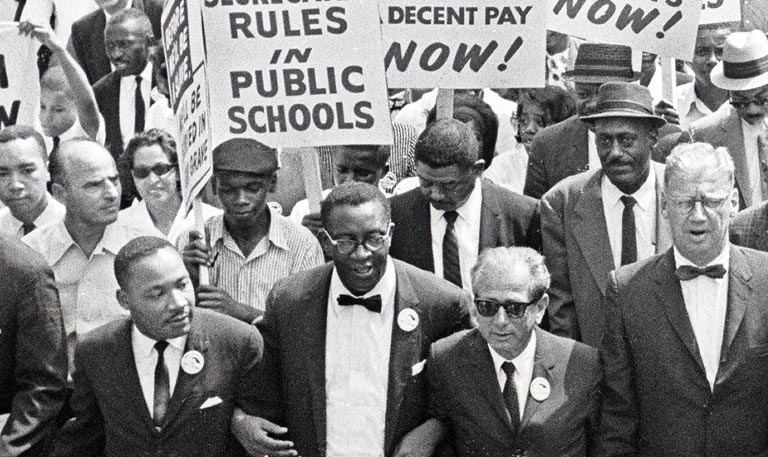

Try tracing how your own comfort levels have adapted over your lifetime. The 1950s brought the beginnings of racial integration, the 1960s fostered individualism and feminism, the 1970s recognized the rights of the disabled and homosexuals, and the 1980s introduced children’s rights. Animal rights rose to the fore in the 1990s, and human rights in general—including the right to healthcare—gained attention in the 2000s. And in our current decade, we’ve seen a focus on immigration and race relations (again) and transgender rights. Looking ahead, the rights of workers and prisoners may find new footing in the 2020s. Have you gotten stuck at any point?

Some cultural changes are easier than others, but too often, gut feelings challenge common sense. Seniors have experienced racial, gender, and ethnic myths crashing down around us throughout our lives. It is understandable that some of our acquaintances and leaders— especially people losing cultural, economic and political power—have retreated to tribalism or nostalgia for a cruder, simpler time. Poverty and war also push people back down to Maslow’s base survival level.

If we still live with anxiety it may be because of the normal disorientation of rapid movement through Maslow’s hierarchy. We have lived through the most extraordinary era of technological, economic, demographic and cultural development in history. People in agricultural economies had more than a century to adapt to the strains of the Industrial Revolution, but we have had only decades to adapt to our global technological and economic web.

It is easier to accept a cell phone or solar panels than to ask, “Who am I? Who have I been? Who do I respect as a human being? Am I mortal?” (Or my favorite, “What’s it all about, Alfie?”) You know where you are among Maslow’s levels, but all of us move up and down depending on our fears.

The top level of Maslow’s original human development ladder was “self-actualization.” Essentially, be all you can be. Find yourself, find a soul mate, love your inner child, find your passions and purpose. Our generation was given a gift—the time and direction to ask deeper questions about life. If a well-stocked fort or many fancy bigger forts is not enough, then what is? Who gets stuck and why?

We seem surrounded by what Buddhists term “hungry ghosts,” a euphemism for empty suits stuck at the survival stage of human development. No amount of money seems to satisfy their hunger or increase their civility. They prove Maslow’s conviction that humans need to feel safe, that they belong, and that they are loved before they can move toward self-actualization.

Before his death in 1970, Maslow offered one more level of human development, a new top for his pyramid—transcendence. He defined it as the ability to find meaning beyond self. Commentators and philosophers continue to ask: Are we connected to all living things? Is the most moral path a belief in quality of life for everyone and everyone everywhere? Where are we, given that people are currently scattered at every level of this human development hierarchy?

What can I offer for your future? The path we have been on, since the first upright primate, is that of civilizing our feral instincts. Civilization can be defined by access to information, acceptance of diversity, and alternatives to violence. The Masai in the Serengeti have satellite access to the internet. For a few years, an African American was president. Our grandchildren accept the value of communication, counseling, mediation, treaties, and international organizations. Civilization will continue to progress aided by our new dependence on a global market. At the most basic level, only a stable shared global economy will fulfill enough human needs.

Try not to mind the absurd zigzags of cultural adaptation. Two steps forward and one step back is the usual dance of cultural life. Turn to the wisdom teachers who, from the earliest records, have agreed that true wisdom is kindness. In your last decades, if you are otherwise safe, your future is to be kind to yourself and all living things.

Jennifer Jameshas a doctorate in cultural anthropology and master’s degrees in history and psychology. She was a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Washington Medical School. Jennifer is the founding mother of the Committee for Children, an international organization devoted to the prevention of child abuse worldwide.