Navigating ageism and changing socioeconomic status’ impact on quality of life.

At some point, we map out a plan for our lives. It might be a vague concept or a set of specific goals, but either way, we generally hope for a life that makes us happy, allows us to control how we work and live, and that we achieve reasonable socioeconomic status that lets us feel successful.

Achieving those goals, including the social or professional status that comes with success, contributes to healthy aging. In cases where we gain years but lose part or all of our status, the way we navigate the change makes all the difference to our happiness.

Socioeconomic status is a key element in quality of life for older adults, according to the American Psychological Association. Long-term illness or a spouse’s death may cause a loss of financial standing that affects where and how we live, even our friendships.

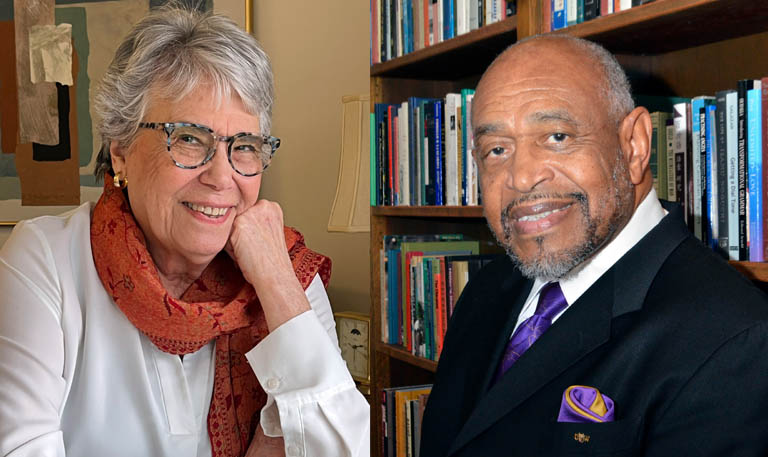

Barbara Craveiro grew up on a dairy farm in Whittier, Calif., with parents who gave their children a wonderful life. There were trips to go boar hunting with grandparents on Maui, weekends in Palm Springs, a university education for Craveiro, and a trip to Europe for her graduation gift. With a double major in education and sociology, she became a third-grade teacher and loved it, but that was only part of her life goal. “I definitely always wanted to marry,” she says. She was 24 when she met Kellogg Metcalf.

“He was a blind date for the 1961 Rose Bowl game,” says Craveiro. “A good friend of mine set us up.” The University of Washington Huskies were playing that year, and a group of Kellogg’s friends had come down from Seattle.

“I spent the next two days in a whirlwind with these people, going all over LA. When Kellogg left, he said, ‘We’ll keep in touch.’” By October, they were engaged, and Craveiro began a new life in Seattle.

“With my father’s help, we bought the Foley Sign Company. Kellogg worked hard and we became successful. We had a good life,” she says.

That life included a home on Mercer Island, four children, and many friends. Craveiro volunteered for just about everything—her children’s schools, fundraising galas for the arts, hospital work, and the Seattle Milk Fund. She and Metcalf traveled internationally and enjoyed summers at their cottage on Whidbey Island. Their kids went to college and started their own careers and families. And then, in her 60s, everything began to change.

“Kellogg got sick—diabetes, congestive heart failure—and went downhill for about 20 years,” she says. “We went through our savings. His illness took up a lot of our resources.” By her late 70s, their finances were in crisis. They sold both their houses and started renting. “We tried to stay on Mercer Island, because that was where my life was, and my connections—church, friends, everything. But then we knew we should move, because money was getting tight.”

After living for a short time with their daughter, Craveiro found an apartment in Seattle, at a SHAG property that provides affordable senior housing.

“When we moved to SHAG, I left a lot behind,” says Craveiro. “Kellogg was here for four days, then went into the hospital and died a few months later. While he was there, and I was here, I thought, ‘Well, I’d better get out there. This is where my new friends are going to be. I’m not going back to Mercer Island.’”

Her first social effort didn’t go well as she attended a dinner for apartment residents and was rebuffed when she tried to find a seat. Eventually, though, she made friends in her new home, and she stayed connected with her old friends as well. There were major adjustments to make, but at 86, she’s truly enjoying her life.

“I’m very content where I am. I’m very grateful for my friends. It’s fun to laugh and reminisce, to just be where we are,” says Craveiro. “I wish I didn’t have to watch my spending so carefully, but that’s so minor. I love where I am.”

~

According to the National Institute on Aging, a longer work/career life has a role in maintaining cognitive function. It contributes to a sense of purpose as well, as we continue to have a positive effect on our communities. However, the attitudes of both employers and colleagues toward older workers can be adversely affected by ageism, including the assumption that age defines both our preferences and our ability to do our jobs.

In her book This Chair Rocks, author and activist Ashton Applewhite points to research showing that “older employees are enormous assets to enterprises of all kinds. Veteran workers also tend to bring valuable experience to the table, as well as honed interpersonal skills, better judgment, and a more balanced perspective.”

Unfortunately, that truth isn’t always understood in the workplace. Older workers who lose their jobs, or must reenter the workforce after retiring, often come up against ageism in the hiring process. “Every day,” says Applewhite, “older job seekers confront myths about their skills, health, and capacity.”

Belief in myths shows up in both blatant and subtle ways, and in unexpected places. In a job-seeking workshop for “older” workers put on by the Washington State Employment Security Department, the 40-something instructor made a joke about the “no texting in class” rule. No one reacted, and she said, “Nothing? We usually get a laugh, because people in this class don’t normally text.” Since almost everyone had been texting or emailing on their phones when she walked into the room, the instructor was both ageist and completely clueless. She also explained that no one should use words on their resumes that might indicate age, making the entire class uneasy about showing their true depth of experience.

Even on a university campus, an individual’s lifelong achievements may not always receive the respect they deserve from those who follow and benefit.

In 1967, Emile Pitre was a graduate student at the University of Washington, one of only 63 Black students on campus. He pictured a future in science, possibly as a professor. Then his life began to change.

“There was the Vietnam War, and napalm bombs, and I became less enthusiastic about being in chemistry,” recalls Pitre. “I began to see the oppression of third world people. My goal was to be a revolutionary.”

It was a time of change for many on the UW campus. In November 1967, 30 black students attended a Black Youth Conference in LA. They came back inspired to work for equity and inclusion in their own community, and on January 6, 1968, they announced the birth of the Black Student Union (BSU) at UW. Pitre was one of its founding members. The students were very serious about what they were willing to do for social justice. The death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. strengthened their resolve.

“We felt like we were warriors, and if we had to die for it, so be it,” recalls Pitre. “We knew that what we wanted to do had to happen. The time had come.”

On May 20, 1968, BSU members took over UW President Charles Odegaard’s office, determined not to leave until their demands were met. After a four hour sit-in, Odegaard agreed to everything they asked. The university would recruit more underrepresented students, set up a Black Studies program, create a minority resource center, and increase the number of Black faculty members, administrators, and counselors.

The UW established the Office of Minority Affairs and Diversity (OMA&D), including an Instructional Center (IC) to support students. Pitre worked there as a chemistry instructor, eventually becoming the IC’s director and an associate vice president. He built a strong team of tutors, began collecting data to track their students’ success, and won awards for instructional excellence. Many of his students went on to impressive careers, and he is immensely proud of their achievements.

As Pitre neared retirement, one part of his work was not giving him joy. As OMA&D’s advisor to the Black Student Union, he began to feel that a new generation was not interested in his experience in activism and political consciousness. BSU leaders would have executive meetings and not include him, and finally he decided to step away from the organization he helped create. “They had no knowledge of what I and others had done. They weren’t listening to what I had to say, didn’t think it was worthwhile,” he says.

In 2014 Pitre retired but returned to the university within a few months to begin writing the history of OMA&D and the early diversity movement at the UW. His book, Revolution to Evolution, tells the story that began in 1968.

“When I get to the end of my life, I want to say I did a pretty good job,” he says. “There’s still work to be done. I’m still an activist, still fighting on behalf of people who need me.”

There are other myths to challenge as we progress through our third act. For example, the things that are considered “age appropriate.” Margaret Hughson, an exquisite woman who had recently moved into a congregate care residence, questioned the assumptions of employees. She disliked the way nurses and other staff spoke to residents, in an overly “kind” voice they’d use to talk with small children. She noted that older people wouldn’t be considered “cranky” if people treated them as capable adults. The activities offered there also fit a stereotype. “Why do they think that I would suddenly enjoy crafts and basket making just because I’m older?” asked Margaret.

As we push back against the ageism around us, Applewhite says it’s also important to look at our own beliefs about age. “Start with yourself. All change starts within. Look at your own attitudes toward age and aging. The minute you see a prejudice in yourself, then you start to see it around you.” And then we can start to rewrite the narrative.

“Age is just a state of mind,” says Craveiro. “I have a little less energy sometimes, but I’m who I am and who I’ve always been. Maybe with a little more experience.”

Priscilla Charlie Hinckley has been a writer and producer in Seattle television and video for 35 years, with a primary interest in stories covering health and medicine, women’s and children’s issues, social justice, and education. She enjoys taking a lighthearted approach to serious topi

More on Ageism:

Learn how our hidden attitudes and images of age shape our actual experience—and what that means for the fight against ageism in our article: “Our Inner Ageist,” by Dr. Connie Zweig

In her 60s, Simone de Beauvoir wrote a 650-page book La Vieillesse (1970)—translated as Old Age or The Coming of Age—to reveal the truth about ageing. Read our story by SKYE CLEARY, “Simone de Beauvoir Recommends We Fight for Ourselves as We Age“