By CHARLES E. KRAUS

I got rid of the albums. Several thousand of them. You can add your name to the list of those who counseled me: Hold a garage sale! Put them on eBay! They’re worth a fortune!

Yep, I told these well-meaning types, if I had the time and energy to devote, I might earn a little folding money. Sadly, I’m as old as some presidents but without the staff. My wife and I are focused on moving. Somewhere. To a small apartment, an assisted living space, to a location that can accommodate folks in old age. The specifics have not yet been determined, but none of the options advertise extra square footage for vinyl discs. Instead of a financial windfall for my records, I ended up paying someone to cart them to the Goodwill.

They can take my albums, but they ain’t getting my books. Thus, I’m struggling with a bibliophile’s dilemma.

I’m still reading and writing. Still collecting. (Don’t tell my wife. There is supposedly a moratorium on new book purchases.) On occasion, I have let go of various tomes. Disappointers that turned out to be less than their reputation would have it. I’ve shed some excess—I once felt it was necessary to collect an author’s entire bibliography. Salinger had only four published books—that was easy. John Updike wrote 60—that is a lot of shelf space.

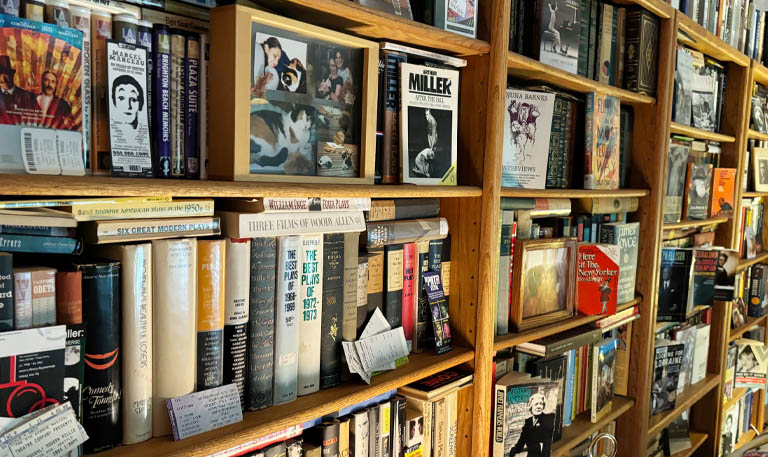

I defend my decision to hang on to the 12 floor-to-almost-ceiling bookcases, plus a few modest hutches for the overflow. The approximately 200 feet of shelving supports a concept called “my library.” Again and again, these books have sent me into the world fortified with insights and bursting with questions.

Certain novels, Sophie’s Choice, for example, were so difficult to read, so sad, so real, so unsettling that they took me ages to finish. I could only digest a page, a paragraph, a scene, at a time. Other fiction was impossible to put down. How could you read Slaughterhouse Five with anything other than a dedication bordering on obsession?

There are horribly written books in my library, but they are the best I’ve been able to find on particular subjects. I’m prone to zooming in on enthusiasms. My interest in exploited rock and jazz artists during the 1950s and ’60s got me looking for books about an assortment of unscrupulous record companies and singers like Jackie Wilson and Jimmie Rodgers, and musicians like Count Basie, all allegedly shortchanged by organized crime. I no longer own their records, but I hold onto the written accounts of the stories behind them.

Hold up any of my books and I can tell you what it’s about and how it found its way to my library. My set of Masterplots, purchased in the ’60s, came from the original Strand Book Store when it was a mere corner shop at East 12th Street and Broadway in New York City. It offered books stamped “reviewer edition, not for sale,” and when I was a young teen, buying one felt akin to a clandestine transaction.

Long before you could locate copies of almost any book online, I spent years putting together the complete works of the better-known New Yorker humorists—Robert Benchley, James Thurber, et. al. Coming across Crazy Like a Fox, which completed my S.J. Perelman oeuvre, I took a deep breath, patted myself on the back, and went to work on E.B. White acquisitions.

While living in the West, I made regular runs to Acres of Books in Long Beach, Calif., comprised of three dusty, poorly lit warehouses containing endless rows of makeshift bookcases. I asked one of the elderly clerks there if he thought there might be any Maxwell Bodenheim books. Sure, he said, providing detailed instructions to the third warehouse, second row about halfway down, right side, top shelf, to the left. That’s how I got Duke Herring, Bodenheim’s 1931 novel.

One last bookshop reminiscence, though I could go on. I’m in Seattle on a rainy fall afternoon browsing my way through a secondhand bookstore. What a wonderful music system, I’m thinking. Amazing fidelity. I look up and find that the proprietor is at his upright accompanying my perusal.

When I think of Dickens, I recall attending high school in Massachusetts, our class sitting by a lively country fireplace, snow falling on the Berkshire Mountains, and Mr. Allen reading from A Christmas Carol. My books conjure up sounds and friends and memories along with stories and ideas.

Aunt Lily gave me Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain for my high school graduation. Her present was so much more than 400-plus pages of information. It was an introduction to the author’s world, his life, his views. Boy did my aunt start a landslide. I’m one of Mr. Twain’s best customers. Often when I’m reading him, I hear my father. Dad read many books to me, including Tom Sawyer. I also hear the voice of Hal Holbrook, whose “Mark Twain Tonight” I attended during four decades of the actor’s stage transmogrifications into Samuel Langhorne Clemens’ alter ego. And Holbrook’s memoirs about becoming Twain—I have those as well as the letter I received from the actor in response to my note. Book collecting is expansive.

Certain works are masterpieces. The sentences, the ingenuity, the juxtaposition of words and thoughts so brilliantly executed that I’m calling people to quote what I’m reading, emailing copies, returning to specific pages and paragraphs, underlined, of course, from time to time, because an author rouses my spirit, comforts me, or simply makes me smile and smile and smile as the years go by.

Walking into our living room, with eight bookcases lining a far wall, I know the place is alive with ideas that took thousands, perhaps millions, of hours to conceive and communicate. Many of the authors have died, but their thoughts, intentions, explanations, explorations, confessions, passions, conjectures, and questions still influence conversations I have when friends drop by. They also instill circumspection as I sit alone, book in hand, communing with a small portion of the transmitted experience.

Sadly, the prospect that I’ll retain my entire collection may be delusional. There are backup plans and strategies for preserving the essence of what I’ve built during 65 years of book collecting. Keep absolute favorite authors and discard the rest? Norman Mailer and Susan Sontag—do they go? Hang on to William Manchester, toss Stephen Ambrose? Perhaps only Booker- and Pulitzer Prize winners? For a while, I considered liberating a few categories. How about the oddball humor books like Richard Armour, and Irvin S. Cobb? Max Shulman, and H. Allen Smith? Probably, I couldn’t give their books away. Should I? What if they ended up in the trash bin behind Half Price Books? How many copies of Don’t Get Perconel With a Chicken are left in this world? And, yes, that is the actual title. Could it be that I end up discarding the very last one?

My best backup plan seems to be to hire a skilled photographer to snap pictures of each bookcase. Clear, sharp images of my collection, full color, with those little mementos—theater tickets, bookmarks—filling incidental shelf space. I retain a hundred books and donate the rest of my collection to the community by holding a series of come-and-get-it open houses designed to place my books in the hands of other collectors. I find a craftsperson, service, printer, or commercial artist who can turn the pictures into life-size wallpaper. Then, no matter where we end up, I can walk into our next residence and feel at home.

Based in Seattle, Charles E. Kraus is a writer, entertainer, and memory improvement teacher. Charles is the author of Baffled Again … and Again, a collection of essays. His most recent book, You’ll Never Work Again in Teaneck, NJ (a memoir) is available in local libraries and on Amazon.

This piece was previously published in the Boston Globe

More insightful essays by Charles E. Kraus: